The COVID-19 health and economic crisis has once again focused attention on the fickleness of capital flows and the need to have an adequate policy toolkit to manage the risks that stem from these flows, while maximizing their benefits.

A virtual workshop organized by the Bank of England, Banque de France, International Monetary Fund and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) highlighted risks emerging from the changing landscape of global capital flows and the need for greater international efforts to address these including by broadening the regulatory perimeter.

The nexus between the global financial cycle and extreme capital flow episodes, as well as currency crises, is here to stay.

Capital flows during the COVID-19 crisis

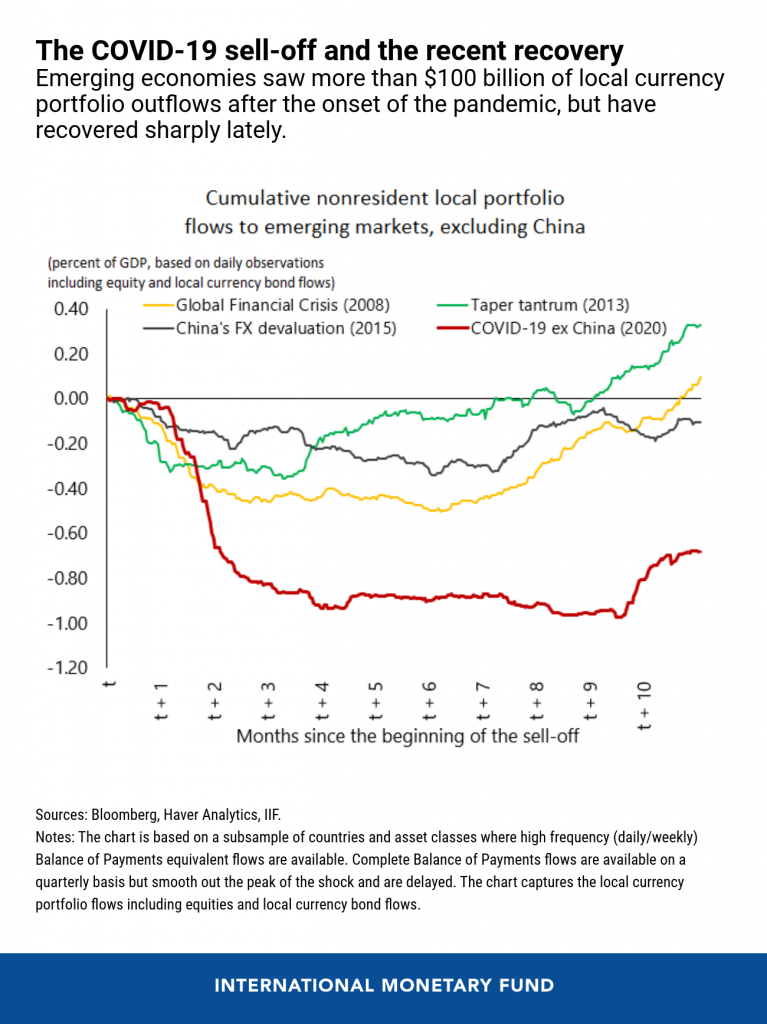

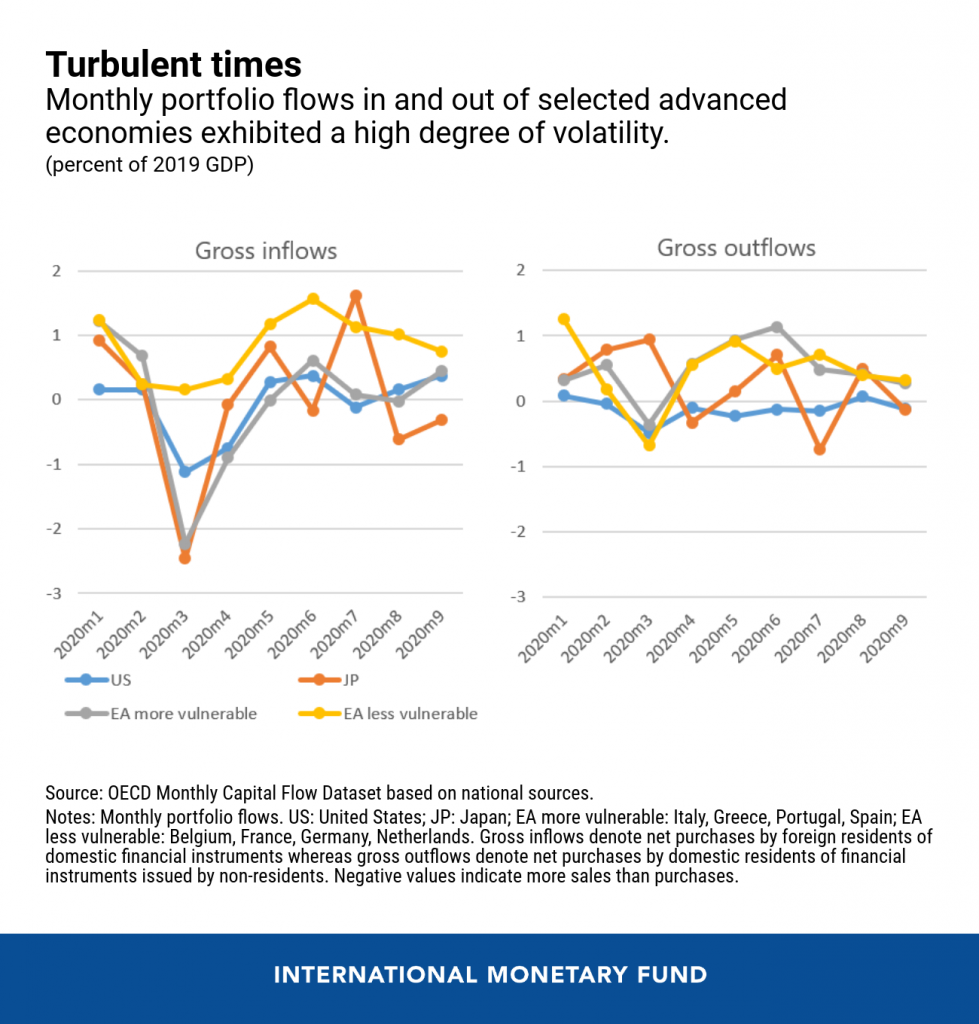

Compared to previous episodes of financial stress, the sudden stop in portfolio flows to emerging markets in response to the COVID-19 pandemic appears to be particularly pronounced. Record capital outflows led to depreciating exchange rates, higher funding costs and limited access to external financing in many emerging markets. Advanced economies, including some euro area economies and Japan, also experienced significant non-resident sales of portfolio assets in March 2020.

The outflow of portfolio capital in emerging and advanced markets was sharp but short-lived. It was cushioned by significant central bank actions including continued monetary easing which was accompanied by large-scale asset purchase programs and increased liquidity operations in advanced economies, as well as foreign exchange interventions in emerging markets.

While banking inflows slowed sharply, the decline was lower than during the global financial crisis in 2008, reflecting the resilience of a better-capitalized global banking sector and the release of counter-cyclical capital buffers by regulators. The decline in foreign direct investment flows, on the other hand, was even more pronounced than during the global financial crisis, reflecting growth concerns in emerging markets.

The new geography of capital flows

The 2008 global financial crisis was a watershed event that exposed the weaknesses and excessive risk-taking in the global financial system, in particular by banks, and led to major regulatory reforms increasing the resilience of the banking systems.

The increased use of offshore financial centers to channel cross-border flows, including by multinational banking groups following greater regulation of the banking sector since the global financial crisis, highlights the importance of continued international efforts to end tax avoidance and evasion, and to broaden the regulatory perimeter.

To facilitate recovery, major central banks have maintained an accommodative monetary policy stance since the global financial crisis. Low U.S. interest rates have led to greater risk-taking by global banks, as they lend more to riskier borrowers in emerging markets and advanced economies. There has been a steady build-up of corporate and sovereign debt in emerging markets and several advanced economies are witnessing housing price appreciation from substantial capital inflows.

While this poses policy challenges, there is evidence that certain supervisory powers can materially dampen this risk-taking. That is, micro-prudential tools can have systemic effects and are important complements to macroprudential policy in strengthening financial stability.

Global Financial Cycle and Policy Responses

The nexus between the global financial cycle and extreme capital flow episodes (sudden stops, flights, retrenchments, and surges), as well as currency crises, is here to stay.

A capital flows-at-risk framework can help policymakers better understand tail events in capital flows in order to take early action to mitigate the risks. Such a framework can be informative about the risks posed by different types of capital flows, shedding light on the way they are intermediated and on the effectiveness of policy responses.

Policymakers are increasingly relying on multiple policy instruments to deal with capital flow volatility. These include monetary policy, macroprudential policies, foreign exchange interventions, and capital flows management measures. The question of which policies—or combination of policies—are most effective in mitigating the risks of sharp capital flow movements generated by global shocks, and the near- versus medium-term trade-offs of different policies, is an important one, and this is part of the IMF agenda on the Integrated Policy Framework.

The global nature of recent crises highlights the desirability of a coordinated international response to mitigate the effects of cross-border spillovers, as well as the need to address the risks posed by economic agents that are outside the regulatory perimeter, in particular nonbank financial intermediaries.

Recent multilateral initiatives such as the swap lines between the U.S. Federal Reserve and some foreign central banks, the enhanced IMF lending facilities, efforts to coordinate regulatory responses including on nonbank financial institutions under the umbrella of the Financial Stability Board and the G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative for the poorest countries are helping mitigate risks. Discussions on the challenges of capital flows in international fora, such as the G20 International Financial Architecture Working Group, the Advisory Task Force on the OECD Codes in relation to the OECD’s Capital Movements Code, and the IMF in relation to its institutional view on capital flows can facilitate the design of appropriate policy responses.

The full list of authors:

Annamaria Kokenyne, Gurnain Pasricha (IMF)

Annamaria De Crescensio, Etienne Lepers (OECD)

Dennis Reinhart, Ambrogio Cesa-Bianchi, Mark Joy (Bank of England)

Julia Schmidt (Banque de France)

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the corresponding institutions.